During most federal court cases in the US, the public gets a visual sense of what is happening through pastels on a canvas, not through the lens of a camera.

Cameras and other recording devices have been prohibited for decades in the vast majority of US federal courtrooms, leaving a record of proceedings in the hands of sketch artists.

Their work is done under intense pressure. The images are usually filed at the hearing’s next adjournment which means they can appear on front pages and cable news channels within minutes.

This was the case in Miami when Donald Trump heard 37 felony counts read out which allege he mishandled classified government documents.

Three veteran illustrators had front-row seats but their depictions of one of the most photographed men on the planet were quite different.

They each explain to the BBC how they go about this unique task.

Bill Hennessy

Over a career now in its fifth decade, William J Hennessy Jr has drawn Mr Trump in various settings – at a Supreme Court judge’s swearing-in, after his second impeachment, and even from footage of the US Capitol riot.

But this week critics accused Mr Hennessy of making the 77-year-old in the Miami courtroom look far younger and trimmer than he really is.

“I don’t put any editorialising into it,” the Virginia native, 65, responds. “I draw it as I see it because I’m there, because the camera can’t be there.”

Feedback is to be expected in such a high-profile case, he says, adding that members of the public pleased with the sketch have written him emails too.

Mr Trump – who has seen his fair share of courtroom interiors – was “fairly stoic”, says Mr Hennessy, not scowling or grimacing but just looking like he wanted to get it over with.

Since covering the 1980 assassination of an Iranian dissident in Washington DC, he has sketched for all manner of cases but mostly covers criminal cases.

Cameras have been limited in the courtroom since a media circus nearly derailed 1935’s so-called trial of the century, over the kidnapping and killing of aviator Charles Lindbergh’s baby.

Now, nearly every US state court allows electronic devices and even some federal district and circuit courts permit their use. It’s a trend that has Mr Hennessy concerned.

“For a lot of people, court becomes entertainment. For me, it’s news,” he says. “What I’m covering usually is very serious and not intended to entertain.”

Jane Rosenberg

If Mr Hennessy is choosing to ignore criticisms of his work, it’s a strategy that has served Jane Rosenberg equally well.

In 2015, she was mocked and bullied by online trolls who said her court sketch from the “Deflate-gate” trial had made NFL star quarterback Tom Brady look like Lurch from the Addams Family.

Mea culpa, she told the New York Times, with tongue firmly in cheek, “for not making him as good-looking as he is”.

Speaking to the BBC this week, she says critics should realise that the job is hard.

Faced with very tight deadlines, stressful courtroom restrictions and no tolerance for creative freedom, the artists all do the best they can, she says. “I’m working my butt off in court.”

Trained as a fine artist, Ms Rosenberg loves to draw people. In addition to thousands of court scenes, she also paints “en plein air” (outdoors) and displays work at a gallery in Massachusetts.

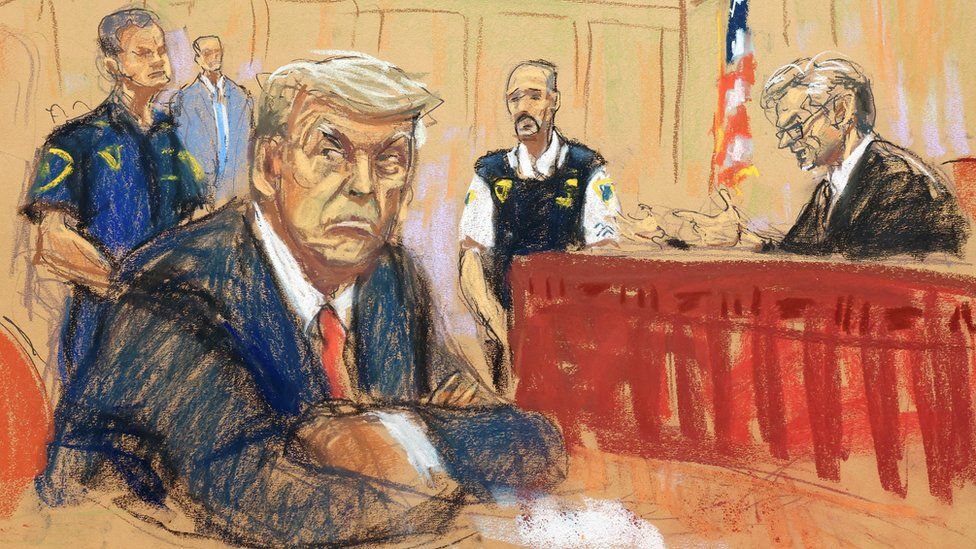

In what she has described as the “most stressful assignment” in her 43-year career, Ms Rosenberg earned a New Yorker magazine cover for a sketch in which she captured Mr Trump turning to glare at the prosecutor in his hush money arraignment in Manhattan in April.

Tuesday’s assignment was equally stressful, she says, with security in the Miami courthouse so heavy that she feared she would not get a good seat inside. But she was lucky to end up in the jury box – in her view the best seat in the house.

“The more time I have, the more likely I will be accurate,” Ms Rosenberg notes, but she says it is nearly impossible to plan ahead. “In a trial, I could have somebody sitting there all day long. An arraignment is usually very quick.”

Elizabeth Williams

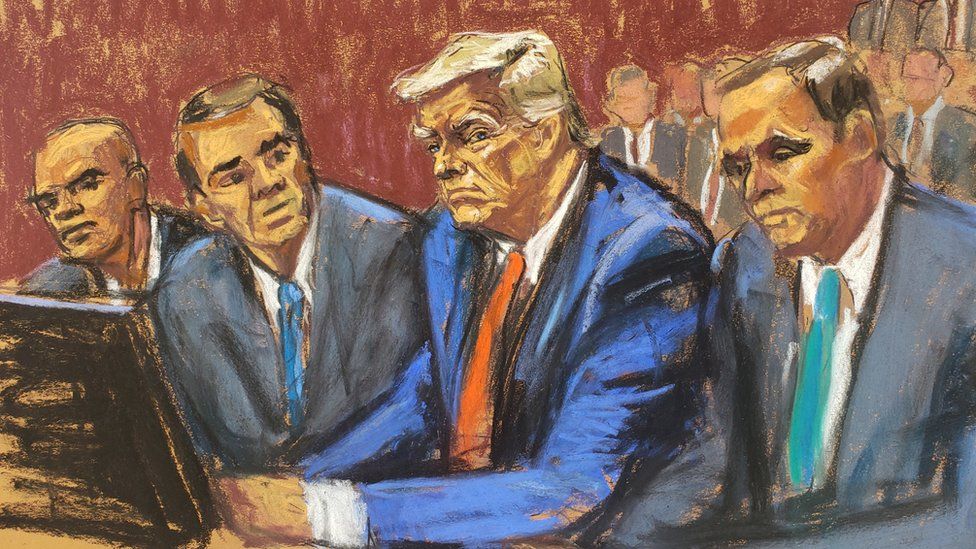

Like Ms Rosenberg, Ms Williams covered both of Mr Trump’s arraignments this year.

“The first hearing in Manhattan, he sat there irked and annoyed and somewhat contemptuous of the process,” she says. There was a seething contempt captured by her art.

The Miami court appearance was different, she says, a more defiant Mr Trump who did not speak throughout.

Her first encounter with Mr Trump was in 1987 when he sued to force a merger between the NFL and the US Football League (USFL).

Thirty-six years later, he does not look like his age, she notes. “I think I’ve got worse bags on my face than him and he’s quite a bit older than me.”

Originally a fashion illustrator, Ms Williams has seen every kind of character in court, from drug kingpin El Chapo’s wife (“it was like drawing a Barbie doll”) to rapper Tekashi69 (“he had such charisma!”).

She calls herself a “visual reporter”, faithfully informing the public what went on and complementing the words written by news media.

“Authenticity is extremely important,” Ms Williams says. “I’m like a substitute camera, drawing what a photographer would shoot. There’s no making stuff up.”

But she believes her profession is a dying art.

“I don’t believe for a minute that we’re going to be doing this in 10 years from now.”